When you look at this picture, what draws your eye? The head shape, the open mouth, the strong mascara?

When you look at this picture, what draws your eye? The head shape, the open mouth, the strong mascara?

For me, what makes this picture so stunning is how it shows off this cat's incredible body.

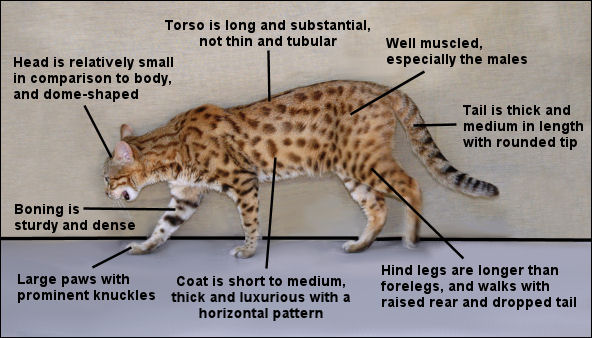

The body of a Bengal cat is an amazingly complex structure that is difficult to produce with consistency. When all the elements come together correctly, the Bengal moves like a fox and looks like no other domestic breed of cat.

One telltale feature to indicate a Bengal has a good body that is easy for everyone to see - head to body proportion. The head of a Bengal cat should be slightly small in proportion to its body - which is the first giveaway that this young cat will have one amazing body.

The other easily discernible trait of a Bengal cat's torso is its shape. The torso should be deeper at the rear end than at the front end, which, once again, is clearly evident in this picture.

So far, this sounds pretty simple. Small head to body ratio and deeper at the rear than in the front - no problem, right? Wrong.

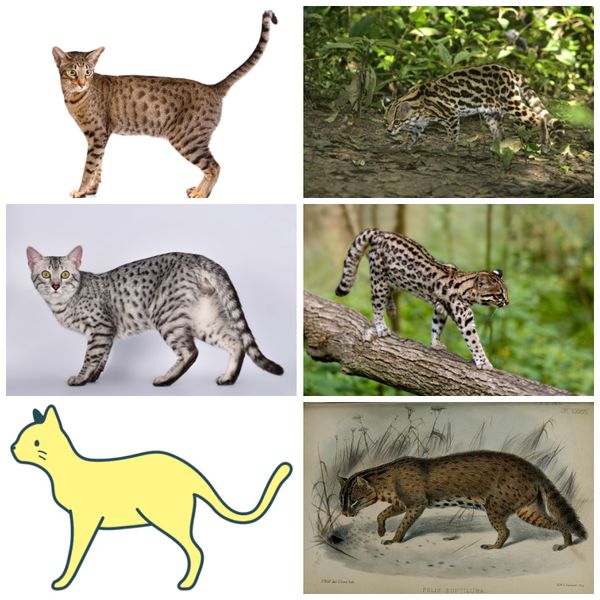

The difficulty is that the body shape and proportions are not typical on domestic cat breeds while normal for a small forest-dwelling wildcat. Leopard cats specifically, not even all small forest-dwelling wildcats, have this shape because of their environment, so keeping the right shape and proportions is hard to do in the Bengal breed. There is a picture of an Ocicat, an Egyptian Mau, and a drawing of what would be considered a generic domestic cat on the left side of the collage from top to bottom. The TICA Ocicat standard calls for a deeper body at the chest; the Egyptian Mau standard calls for a balanced body, and the drawing of the cat is simply the artist's depiction of what a normal cat body looks like. Domestic cats tend to have bodies equal in depth from front to back or deeper at the front end around the chest.

There is a picture of an Ocicat, an Egyptian Mau, and a drawing of what would be considered a generic domestic cat on the left side of the collage from top to bottom. The TICA Ocicat standard calls for a deeper body at the chest; the Egyptian Mau standard calls for a balanced body, and the drawing of the cat is simply the artist's depiction of what a normal cat body looks like. Domestic cats tend to have bodies equal in depth from front to back or deeper at the front end around the chest.

But not the Bengal, and the reason why is pictured on the right side of the collage. On the right side, the top picture is a Margay; the middle picture is an Oncilla, and the bottom is an artist rendition of a Leopard cat. Small wildcats who live in trees have a deeper back end to their body - with the Leopard cats having the deepest body of all.

Why is it that the small forest-dwelling wildcats have a depth to their body at the back end and not the front? Let's look at the top line of a Leopard cat and a Bengal cat.

There should be a lot of length to a Bengal's body. Once the spine transitions from the thoracic to the lumbar vertebrae, it gently rises into a slight arc. Why is this? Partially, it is due to the small forest-dwelling wildcat's longer back legs. The longer rear legs mean the back must rise with them. But it is also partially due to the positioning of the pelvis on the small forest-dwelling wildcat. As mentioned previously, Mother Nature is the designer of the wildcat, and the survival of the fittest shapes all wildcats. The small forest-dwelling wildcat's rear end is designed for ease of jumping from tree to tree. A 2002 research study on the correlation of domestic cat morphology and jumping ability concluded that cats with longer back legs and a lean body mass were the most proficient jumpers, which would explain why arboreal cats have longer back legs. But a handful of domestic cat breeds have slightly longer back legs, so there is more to it than just the length of the back legs.

As mentioned previously, Mother Nature is the designer of the wildcat, and the survival of the fittest shapes all wildcats. The small forest-dwelling wildcat's rear end is designed for ease of jumping from tree to tree. A 2002 research study on the correlation of domestic cat morphology and jumping ability concluded that cats with longer back legs and a lean body mass were the most proficient jumpers, which would explain why arboreal cats have longer back legs. But a handful of domestic cat breeds have slightly longer back legs, so there is more to it than just the length of the back legs. The second factor contributing to the shape of the Bengal's spine is the pelvic bone placement. Since the pelvis contains the hip socket, noticing the hip placement can give you clues about where the pelvis is on your cat and how it is positioned. Start paying attention to where a Bengal's hips are placed. The further back they are, the closer that cat's structure is to its small forest-dwelling wildcat ancestor. Notice in the collage of the Margay and the domestic cat that the leg of the Margay in the top picture joins the pelvis way back where the spine curves down at the end of the cat, and the femur angles distinctly forward back under the cat; in contrast, on the domestic cat, the leg joins the pelvis up high and slightly further forward on the body. There is no downward curvature of the domestic cat's spine, and the femur angles more straight down towards the ground. The tail is a good indicator of the positioning of the pelvic bone. On the domestic cat, the pelvis is relatively flat and nearly aligned with the back. On the Margay, the pelvis is angled down at about a 45-degree angle. This is seen by the spine's downward curve and the tail that is set down low after the spine turns down.

The second factor contributing to the shape of the Bengal's spine is the pelvic bone placement. Since the pelvis contains the hip socket, noticing the hip placement can give you clues about where the pelvis is on your cat and how it is positioned. Start paying attention to where a Bengal's hips are placed. The further back they are, the closer that cat's structure is to its small forest-dwelling wildcat ancestor. Notice in the collage of the Margay and the domestic cat that the leg of the Margay in the top picture joins the pelvis way back where the spine curves down at the end of the cat, and the femur angles distinctly forward back under the cat; in contrast, on the domestic cat, the leg joins the pelvis up high and slightly further forward on the body. There is no downward curvature of the domestic cat's spine, and the femur angles more straight down towards the ground. The tail is a good indicator of the positioning of the pelvic bone. On the domestic cat, the pelvis is relatively flat and nearly aligned with the back. On the Margay, the pelvis is angled down at about a 45-degree angle. This is seen by the spine's downward curve and the tail that is set down low after the spine turns down.

To recap thus far, the top line of a Bengal body should be long; it has a long slope curving upwards before turning down at the pelvis then flowing into the tail, which extends off the body. A Bengal needs this top line to stand a chance at developing a body that is deep in the rear. But that is only half the story - the top half.![]() The bottom line of the Bengal contributes to its depth as well. Tree-dwelling cats have this amazing feature that acts as a mini parachute. When falling or jumping down, a cat will spread out its legs to maximize the drag and distribute the force of impact across its body; however, tree-dwelling cats, especially those living in Asian forests where trees are tall and widely spaced, have evolved a larger flap of skin that stretches out further allowing for longer jumps from tree branch to a tree branch as it creates a slight gliding ability due to the increased drag. While all cats have a primordial pouch - loose skin that protects the stomach - on the Leopard cat, it has morphed into a larger feature that gives the Asian forest dwellers the ability to stay in the air a little bit longer to make those long jumps from tree to tree.

The bottom line of the Bengal contributes to its depth as well. Tree-dwelling cats have this amazing feature that acts as a mini parachute. When falling or jumping down, a cat will spread out its legs to maximize the drag and distribute the force of impact across its body; however, tree-dwelling cats, especially those living in Asian forests where trees are tall and widely spaced, have evolved a larger flap of skin that stretches out further allowing for longer jumps from tree branch to a tree branch as it creates a slight gliding ability due to the increased drag. While all cats have a primordial pouch - loose skin that protects the stomach - on the Leopard cat, it has morphed into a larger feature that gives the Asian forest dwellers the ability to stay in the air a little bit longer to make those long jumps from tree to tree. If you look at the picture above of the Leopard cat Icon of Stonehenge walking in front of the kitchen cabinets, you can see the extra flap of skin that extends from his upper back leg to mid-abdomen. That is the primordial pouch. Grab your Bengal; you should be able to put your fingers behind this loose skin. The primordial pouch, however, should never be confused with fat accumulation. A pouch is just skin, nothing else; fat feels more solid and is centrally located between the belly and the back legs. Keep in mind the pouches' purpose, which is to allow the cat to glide to make longer jumps in the trees of the Asian forests; remembering the purpose should help you distinguish between a primordial pouch and fat accumulation slightly. This expanded primordial pouch of its Leopard cat ancestor gives the Bengal body its expanded depth at the cat's bottom line.

If you look at the picture above of the Leopard cat Icon of Stonehenge walking in front of the kitchen cabinets, you can see the extra flap of skin that extends from his upper back leg to mid-abdomen. That is the primordial pouch. Grab your Bengal; you should be able to put your fingers behind this loose skin. The primordial pouch, however, should never be confused with fat accumulation. A pouch is just skin, nothing else; fat feels more solid and is centrally located between the belly and the back legs. Keep in mind the pouches' purpose, which is to allow the cat to glide to make longer jumps in the trees of the Asian forests; remembering the purpose should help you distinguish between a primordial pouch and fat accumulation slightly. This expanded primordial pouch of its Leopard cat ancestor gives the Bengal body its expanded depth at the cat's bottom line.

There is one last feature of the torso which shall not be neglected. The Bengal cat should have a very lean, athletic, muscular torso. There is not one bit of excess bulk on its body. Remember that 2002 study I mentioned above on the cat's jumping ability - the two most important factors were longer hind legs AND a lean body mass. Because Bengals have thick boning, they can sometimes have thick bodies as well. But to be a superior tree-living creature, the cat needs the boning without the additional body mass. The Amur Leopard cat pictured at the top right of the first collage doesn't spend as much time hunting in trees as it mainly hunts on the ground, and the overall thickness of his body is a dead give away that the Amur Leopard cat is not jumping through tree branches to catch its next meal.

To review, the Bengal a long, lean, athletic body that is deeper at the hind end than the front end. The following traits create this body shape:

- Longer spine

- Taller back legs

- The pelvis being set further back and angled downward.

- The primordial pouches

In addition, you want to avoid any excess body bulk as a lean body mass is required to survive in the forest's canopies. When you bring all of those elements together on one cat, you get the ideal Bengal body - one that replicates the small forest-dwelling wildcats of Asia.

These Blogs are written by Robyn Paterson, with much of the content coming from the mind of Jon Paterson. We intend to help other Bengal breeders notice and select features distinct to small forest-dwelling wildcats to better the breed together.

Read More. . .

Rule of Thirds - The Front Third

Rule of Thirds - The Middle Third

Rules of Thirds - The Back Third

Bengal Nose Set

Bengal Nose Size

Bengal Nose Shape